Hello, teacher!

This is the first article in a new series I have decided to write. I recently realised that the knowledge we gain for the concorso (particularly the concorso straordinario ter) is very theoretical. As a result, not only does it feel a bit useless but it is also difficult to remember.

That is why I am now catching two birds with one stone: in this new series of articles titled “Beyond the concorso: turning theory into classroom practice”, I will explain some of the topics from the concorso programme and show you how they can actually be useful for classroom practice.

Every week, I will cover a topic from the concorso syllabus and connect it to a practical teaching application, with examples, case studies, research findings and teaching activities.

Topics will include metacognition (starting with a bang!), assessment, learning theories, individual differences, inclusion and more.

Who will this be useful for?

- Teachers who are studying for the concorso: seeing how the theory plays out in practice will help you understand and memorise (ugh) what you need for the exam

- Teachers who are not studying for the concorso: you will gain lots of practical knowledge, new activities and a deeper understanding of your classroom

The best part: all of this will be delivered for free straight to your inbox every Sunday morning, so you can enjoy it with your coffee ☕ (if you want to be one of the 7,000 people reading the newsletter, sign up here!)

Metacognition and Francesco’s story

Let’s start with a topic that is really key both to the concorso and to learning and teaching: metacognition. It sounds like a big, scary word but I promise you it will be a lot clearer and practical when you get to the end of this reading.

Let me tell you the story of a learner of mine, Francesco (a pseudonym). Francesco is a B2-level student who had a big issue when he started learning with me: he needed to pass the IELTS test to take a university degree in English but he always failed the listening section.

After reassuring him and scratching a little under the surface, I learned that Francesco did *tons* of listening practice, literally test after test. He didn’t prepare much for any of them and while he listened, he often panicked and lost his concentration.

What changed things for him? A new regimented listening schedule with good listening methodology and, of course, a properly pedantic teacher (yours truly): everything he needed to become a metacognitive learner.

What does metacognition mean… in practice?

The term metacognition is traditionally associated with American psychologist John Flavell.

But what does metacognition (metacognizione) mean?

It means “thinking about thinking” 💭

It means knowing about our cognitive processes and being able to control, organise, monitor, adapt and reflect on them.

Metacognition is often divided into metacognitive knowledge and metacognitive strategies.

Metacognitive knowledge is what we think about ourselves as learners, about the task we’re trying to accomplish and about the strategies we can use to tackle it.

For example, we might think of ourselves as naturally bad listeners and we might think of listening as an uncontrollable and unpredictable task.

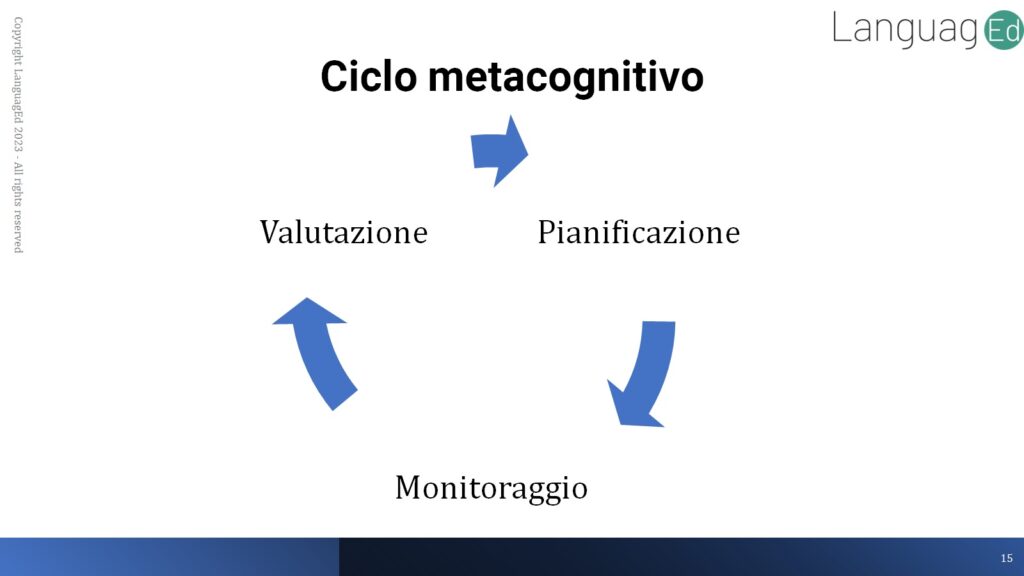

Metacognitive strategies are the executive actions that we take to learn better. These strategies can be of 3 types:

- Planning: what we do before a task. For example, setting ourselves some objectives or deciding what to focus on.

- Monitoring: what we do during a task. For example, monitoring how much we’re understanding as the basis for deciding to ask a question.

- Evaluating: what we do after a task. For example, we self-assess how well we did the task and reflect on what we should have done differently.

Why do we need metacognition, you ask?

Well, first and foremost because it helps us gain control of our learning. If we understand what is happening as we learn, we understand what’s going well and what needs to change: this makes it more unlikely that we’ll hear the usual “ma prof, perché mi ha messo 4??” (the bane of our existence, I know).

Metacognition helps learners become more active and responsible for their learning, which results in better motivation. Plus, gaining control over learning helps them panic a little less, which never hurts.

How I helped Francesco develop his metacognition

So, can you guess what Francesco was doing wrong?

He was doing lots of practice (which was great) but he wasn’t doing it very metacognitively (I swear this word exists).

What did I do to help him?

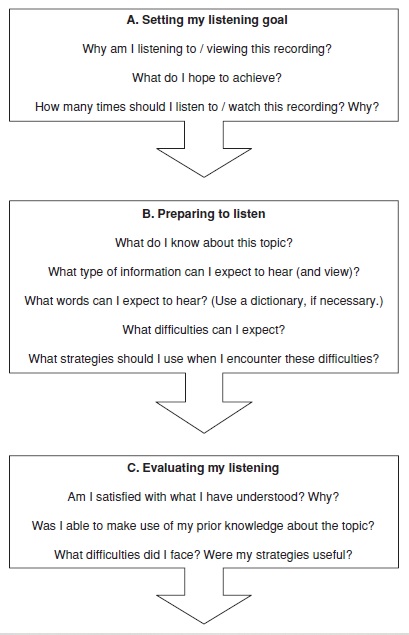

- We diagnosed his metacognitive knowledge: I gave him a simplified version of the Metacognitive Awareness Listening Questionnaire. This is a great starting point to diagnose our learners’ ability to plan, monitor and evaluate their listening.

- We worked on his planning, monitoring and evalutation skills with these activities:

- I gave him a plan: although he was practising a lot, he didn’t have any structure, so he ended up feeling like he had no control over his listening. I gave him a plan to organise his listening so that he actually learned from it: you can download it here and use it with your students too!

I hope this is helpful and let me know if Francesco’s story resonates with your experience!

What other topics would you like me to cover in “Beyond the concorso”?

Let me know in the comments and I’ll do my best!

Ti è piaciuto l'articolo? Condividilo coi tuoi amici:

Grazie Chiara. Sei preziosissima per noi!!! Thanks a loro!!

I’m booking forward to read you again.

Thank you, Mariangela! Your words are much appreciated and I’m glad to hear this work is useful.

All the very best,

Chiara